THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (1996) is very loosely based on the famous Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel NOTRE-DAME DE PARIS and so is a departure from the standard ideal of animations based on fairy tales or children’s books. However, the material is bowdlerized and adorned with fairy-tale tropes sufficiently to appeal to the expected audience, and carried off with craft and wit enough to charm all ages.

Myself, I am one critic who will not scoff at Disney removing horrific elements from the Brothers’ Grimm or changing tragic endings to happy. To me the preference for optimism seems a core feature of the “can-do” American spirit that ran from the colonial days to the generation of the World Wars. Disney, at least during the glory days of their best story-telling, affirmed that spirit, and embraced that optimism.

As one Disney executive put it, when asked about grafting a happy ending onto Victor Hugo’s morbid tragedy, “The American viewing public is not ready for a Disney film where all the main characters are dead by the last reel.”

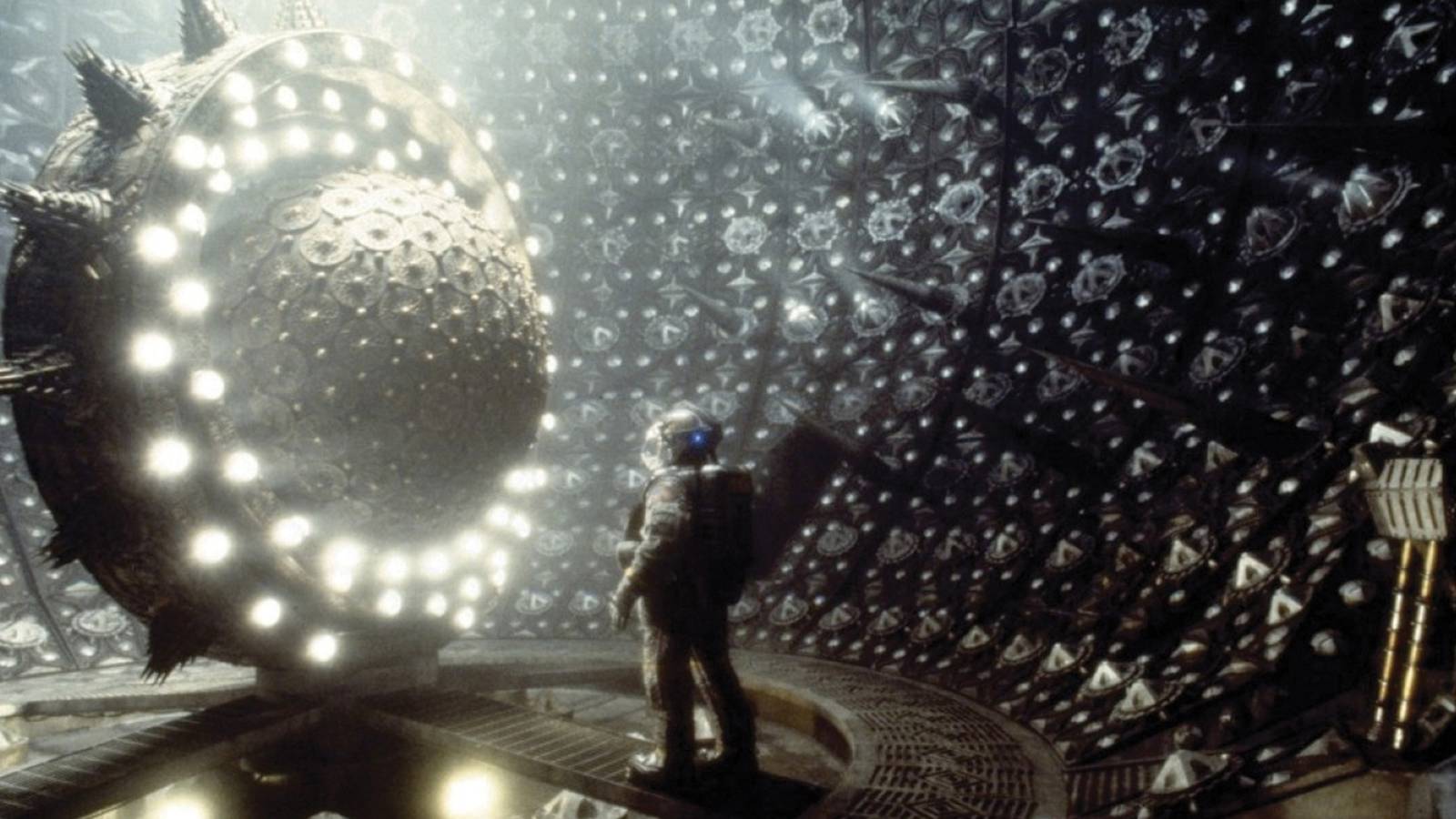

Victor Hugo’s main concern in writing his book was to bring to public attention the ancient beauty of the majestic cathedral at the heart of the story, which, in his day, was in danger of neglect by time or destruction by ill-intentioned renovation. The skill and dramatic framing of every shot and detail of the mighty Cathedral and its brilliant architecture, enhanced by swooping camera work, adorned by a regal soundtrack, illuminated with brilliant special effects such as rippling reflections shining from the famous rose window, could not have done more to excite a love of the beauty of the great building than Victor Hugo’s elaborate descriptions. The Cathedral becomes, in effect, not merely a setting, but a character. This film is a wonder to the eye.

The opening song by Clopin the Gypsy recounts in brief the sad history of the Hunchback: years ago, the wicked Minister Frollo, during a cruel police raid against gypsy trespassers, caused the death of the young mother of a deformed baby, whom he vows, as penance, to raise and father. But the ugliness of the child, Quasimodo, causes him to be confined to the belltower of Notre Dame, where he grows to manhood as the bell ringer. The theme of the tale is here introduced, asking whether being a man or monster is a matter of outward looks or inward spirit.

More than merely well-executed, this musical introduction is a work of enduring genius: upon discovering that what he thought to be a bundle of stolen goods is, in fact, a deformed baby, Frollo steps nigh a deep well, preparing to toss the innocent infant to its death.

The Archdeacon of the cathedral, a chubby and balding man yet depicted as wielding gigantic spiritual authority challenges Frollo, and reminds him that the saints and apostles seen in the statues of Notre Dame are watching him.

The thunder rolls and the music crashes. The camera pans in on Frollo’s panicked face, as the stony faces of holy men and martyrs, and even a stern little Baby Jesus, glare down at him. This is perhaps my favorite moment of any animated film.

Clopin the narrator sings

And for one time in his life

Of power and control

Frollo felt a twinge of fear

For his immortal soul

And, meanwhile, in the background, the choir is chanting the Kyrie Eleison — a cry to the Lord for mercy.

Next, we then see Quasimodo as fully grown, a sad yet goodhearted figure, yearning to see and meet and move among the myriad folk of Paris he can see each day from his high perch in the belltower.

Disney here did a brilliant job of having the brutish deformed hulk look sweet and appealing, despite his monstrous appearance. Not easy to make a hunchbacked cripple look cute without making him cutsie, but the animators here did it.

We are introduced to the comedy relief characters of three gargoyles, Victor, Hugo, and Laverne, comically crude or comically supercilious or comically curmudgeonly-yet-wise, who may or may not be projections of Quasimodo’s solitary imagination.

During the Festival of Fools, Quasimodo sneaks down to the street to participate in the festivities, and his ugly face is mistaken for a mask. Here we see the alluring Esmerelda, gypsy dancer, sensuously swaying to display her voluptuous charms in a fashion Disney dares for no other female character.

Frollo, as the puritanical pinch-nose hypocrite that he is, is bewildered and seduced by the sight, while lust and shame war in his cold heart.

Quasimodo is crowned King of Fools to the applause of the crowd, which, finding his ugliness is not a mask, immediately turns on him with hatred, binding, humiliating, and hurling ripe fruit while he whines and cowers. Frollo lifts no finger to rescue the poor bellringer, but Esmerelda does.

The sad scene follows of Quasimodo, back in the belltower, apologizing to Frollo for doubting his wisdom in saying that the hunchback must forever remain locked away from society, hated and hidden.

We are introduced to Captain Phoebus, who was brought in from the wars by Frollo to organize an ethnic cleansing program to expel the gypsies from Paris, but the brave captain balks at the cruelty and lawlessness of Frollo’s efforts, which are prompted, in no small part, by Frollo’s unholy lust for Esmeralda.

Esmeralda takes sanctuary in the Church to elude arrest, befriends Quasimodo, and reveals to him the secret of the Court of Miracles, where the gypsies are hiding from Frollo’s wrath. Quasimodo is prompted by his gargoyle friends to confess his love for her, but before he can do so, he sees Esmeralda has fallen in love and Phoebus, who, after his inevitable break with Frollo, was wounded when resisting arrest, plunged into the river, and was rescued by the gypsy girl and nursed back to health.

Frollo tricks Quasimodo and Phoebus into leading him to the Court of Miracles. It is called the Court of Miracles because beggars pretending to be blind, crippled, or leprous to fool the kindhearted are miraculously ‘cured’ when they throw off their disguises.

Esmeralda refuses Frollo’s unclean advances, preferring to burn to death as a witch. The most famous scene from the story is, of course, Quasimodo making a daring rescue of the girl from the midst of the execution, retreating to the church, and crying out “Sanctuary!”

Phoebus releases the gypsies and leads a peasant revolt against Frollo, whose mean are besieging the Cathedral. Quasimodo and his gargoyle friends dash boiling oil against the besiegers. Frollo enters alone, pursues Esmeralda to the cathedral balcony, clashes with Quasimodo, and drives him over the edge. Quasimodo clings by his fingertips while Esmeralda attempts in vain to pull him to safety.

Frollo is saved from falling by Quasimodo, who repays this mercy by drawing a sword to slay Esmeralda. He flourishes the blade and quotes scripture to justify his dark deed. As he speaks, his footing fails, he slips, catches a drainspout.

Then the demon-faced drainspout to which Frollo clings comes to life and roars at him with a fiery mouth. The wrath of God Almighty smites Frollo for his wickedness, and he plunges screaming like Lucifer into the fire below.

It is a fitting end, as satisfying as the death of other Disney villains like the evil queen in SNOW WHITE or the Dr. Facilier witch-doctor in PRINCESS AND THE FROG.

Quasimodo sadly blesses the happy couple of Esmeralda and Phoebus, but, urged by his inner gargoyles, is welcomed by the gathered crowds as a hero. A bittersweet but happy ending.

The characters are charmingly drawn, eminently memorable, and expertly voice acted. Tom Hulce captures perfectly the hopeless optimism of Quasimodo half-smothered by a lifetime of solitude and paternal cruelty.

Esmeralda is voiced by the husky and sensuous contralto of Demi Moore, which does not detract from her considerable feminine appeal of the animator drawing her. Disney often draws heroines to be attractive, or did at one time, but this is perhaps the first portrayal of a seductive, smoldering beauty. No prior Disney princess dances to enchant the eyes of men.

When confined to the Cathedral to escape arrest, Esmeralda sings of the poor and outcast who are the children of God, while the camera lingers lovingly over Notre-Dame’s stained-glass windows, soaring arches, images and icons of saints and angels and the Virgin Mary.

It is frankly shocking to see such a clear and striking positive portrayal of Christian faith from Disney.

The attempt may have been to shame the Christian faithful as pharisaic, and the pagan gypsy as virtuous, but, if so, the attempt badly backfires: no scene in any animated film in memory more aptly shows the sweet sorrow and beauty of Christian compassion. (It is not as if Christians mind when Pharisees are compared unfavorably with good Samaritans or gentiles.)

Tony Jay portrays Frollo’s voice in a drawling sneer mingled with false piety that is appalling, occasionally bursting into wrathful or whining self righteousness. His voice forms a perfect picture of a hateful hypocrite.

The scene where he sings to the Virgin Mary to save him from the temptation of Esmeralda is unparalleled in Disney canon. His own self-condemnation appears in a vision of a red robed inquisition while the curvaceous form of Emeralda as if made of dancing hellfire writhes and beckons before his eyes.

Please note the song starts with the prayer of the pharisee from the famous parable:

[Blessed Mary], you know I am a righteous man

Of my virtue I am justly proud

Beata Maria, you know I’m so much purer than

The common, vulgar, weak, licentious crowd

The song begins with the choir of holy men chanting the Confiteor Deo, a confession of sin, while Frollo boasts of his sinlessness. The choir chants Mea Cupla, while Frollo blames Esmeralda’s witchcraft for his fascination with her. It is truly dark, disturbing, and true to life.

Phoebus is portrayed by Kevin Kline who voices a witty, lighthearted devil-may-care swashbuckler tone reminiscent of Errol Flynn.

The archdeacon who holds Frollo to account in the opening scene is voiced by David Ogden Stiers, famous for roles in MASH and STAR TREK NEXT GENERATION as well as portraying Cogsworth or Governor Ratcliffe in prior Disney films.

The musical score was by Alan Menken, with lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (who had previously collaborated on POCAHONTAS). Deeply moving and haunting chants and Latin choirs from Catholic tradition adorn the score at apt points, adding emphasis or irony.

The film’s songs are an honorable addition to the long and triumphant catalogue of classic Disney songs. You may not place any in the top five, but only because Disney’s top five are immortal. But anyone will place these songs above the average even for Disney’s high standards, and well able to raise a cheer or draw a tear.

Songs include “The Bells of Notre Dame” (sung by Clopin) “Out There” (sung by Quasimodo, but Frollo sings the mocking reprise) “Topsy Turvy” (Clopin), “God Help the Outcasts” (a truly beautiful song, sung by Esmeralda) “Heaven’s Light” (a tearjerker sung by Quasimodo), “Hellfire” (Frollo sings the best villain song of all Disney’s villain songs) “A Guy Like You” (sung by the comedy relief gargoyles) and “The Court of Miracles” (sung by Clopin and a choir of gypsies). Phoebus has no songs.

The setting admirably portrays the cathedral in all its magnificence. Disney animators studied the sacred edifice in detail before setting pen to storyboard, and the extra effort shows. Details of medieval Paris, clothing, and housing, as far as my untrained eye can detect, are accurate. If there is any intrusion of modernism into the archaic settings, is it a matter of theme only.

Of modern thematic intrusions, of course the absurdity of having Esmerelda and her ninja goat in fight scenes stave off armed and armored fighting-men: but the incompetence of evil guards is a standard trope of all adventure literature (or otherwise Robin Hood, Zorro, and Han Solo would have been dead from arrowshot, bullet, or blaster-bolt right off).

The plot revolves around the systematic racial persecution of the gypsies, which is somewhat anachronistic. Racial persecution is the hallmark obsession modern day; in the Middle Ages religion was the main driver of persecutions between peoples, not race. (Note that a modern eugenicist, for example, would despise Jews whether converted to Christianity or not, whereas a medieval Inquisition was concerned with faith, not race.)

In real life, gypsies were almost unknown in the Fifteenth Century Europe. A small band of a hundred or so appeared in Paris in 1427 and were a great curiosity. (The novel takes place in 1482). But by the time Victor Hugo wrote, the romanticized idea of gypsies as light-fingered nomadic fortune-tellers, beggars and rogues was well established. Disney merely uses the racial divide as a theme for a morality tale about judging souls not by outer appearance to win sympathy for our hero and heroine.

Clopin in the book is secretly the King of the Truands, the beggars, thieves and outcasts of Paris, and Esmeralda is a girl kidnapped as a child and raised as a gypsy, but the theme of racial bigotry is absent in the book.

The plot and the ending reverses or ignores nearly everything in Victor Hugo’s gothic tragedy. The hunchback, for example, cannot be deaf in Disney for he must sing his songs. He does not throw Frollo from the window in rage after Frollo laughs at the sight of Esmerelda hanged after being framed and falsely convicted of the murder of Phoebus, nor does Quasimodo starve to death in a graveyard while hugging her corpse. On her part, Esmeralda is not besotted with Phoebus, who is a mere philanderer, nor does she wed and save the life of the pedantic poet who wanders unwittingly into the Court of Miracles, Pierre Gringoire (the protagonist of the novel, dropped from the Disney adaptation). Finally, in the book, it is the mob led by Clopin who besieges the Cathedral, not the city guard.

Most of the elements of the Disney version are taken, not from the book, but from the famous 1939 RKO film (starring Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Hara) such as making Frollo the Minister of Justice the villain, and not Frollo the Archdeacon. Esmeralda is alive at the end of the film, and Quasimodo sadly watches her depart with her handsome beloved. The racial persecution angle is an invention, not of Disney, but of this 1939 RKO film version.

Reservations or criticisms are but few to name. The song where Quasimodo’s (perhaps imaginary) gargoyle friends urge him to confess his love to Esmeralda, and promise him she will love him in return, as in BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, is a misstep. It is played for laughs, but it leads to a tragic disappointment, for, in this version of the tale, love does not conquer all. Quasimodo’s deformity cannot be overcome by his innate goodheartedness, or, at least, he does not win the maiden’s heart. The song is a example of the cruelty that comes of fanning false hopes.

Unlike a fairytale or children’s storybook, the source material is brooding and complex, and consist of many flawed characters and no true hero. Disney cannot overcome this entirely, albeit some aspects can be ameliorated.

Even in adaptation, there is no one hero to the film, as Phoebus does not save Esmeralda nor stop Frollo, nor does Quasimodo, but the Cathedral itself, which comes to life first to save baby Quasimodo, and after to damn Frollo and cast him into the fire. Quasimodo’s love for Esmeralda is unrequited even at the end, and she goes off with another, but there is no scene of the heartbroken hunchback whispering to the gargoyles “Why was I not made of stone, like thee?”

But these criticisms are remarkably minor. As with any Disney film, this will be the lifelong favorite of some child who saw it at just the right age, and so the film merits being called a classic, and lauded with high praise. It stands among the other brilliant works of the Disney Renaissance, and is among the better even of that august company.

Well worth seeing, and, like any Disney masterpiece, well worth seeing many times.

Originally published here

English (US) ·

English (US) ·