OMAC, One-Man Army Corps, was Jack Kirby’s short lived near-future superhero comic, sadly unfinished, which ran a scant eight issues from 1974 to 1975.

Kirby was obligated to deliver fifteen pages of finished copy a week, and with the cancellation of his other series (NEW GODS, THE DEMON), so he revisited an old idea with a startling new twist: OMAC might be called CAPTAIN AMERICA crossed with Alvin Toffler’s FUTURE SHOCK (a bestseller from 1970).

His contract for DC comics was about to end: the high pressure and short timespan might explain what seems rushed and improvisational tone in the work.

One grand idea after another is delivered and forgotten as plot points are needlessly repeated, or plot threads are tangled or dropped, albeit delivered with such surreal high-octane high-concept Wagnerian bombast, and Kirby’s often imitated hyperkinetic style, that no true fan of Kirby will pause to note these lapses.

Kirby on his worst day is better than most writers on their best day.

The setting is the true star of the work, for we are introduced to The World That’s Coming, a grim and dehumanizing world tottering on the brink of global destruction, thanks to the perfection of technologies merely theoretical in the present day, but all too likely.

Other might describe this setting as a dystopia, and, had its themes been properly explored, it might have turned out to be: but I prefer that word be used only to refer to worlds that reached the dead end of tyranny or dehumanization as foreseen by Orwell or Aldous Huxley, or atomic apocalypse.

Here, the World That’s Coming is dangerous, disquieting, and corrupt, but OMAC is meant to be a last stalwart and moral icon desperately fighting to curtail the forces of dystopia or apocalypse in “a world stacked with nuclear bombs”— except, ironically, OMAC is a product of dehumanizing technology, and literally so.

Cold War despair about the future, a sense that technological change outstrips human ability to adapt to it, or use it wisely, pervades the work, and is perhaps its most memorable feature.

The plot concerns one Buddy Blank, an aptly named corporate nobody working for a megacorporation called Pseudo-People, who manufacture lifelike love-robots in their Build-a-Friend division.

Lonely, bullied, and mocked, his sole friend is the fair and sympathetic Lila, a girl who turns out, tragically, to be a one-use assassin-robot programmed to seduce a victim and explode at the first embrace.

Gloating corporate goons close in on Buddy to kill him once he discovers this heartless and inhumane conspiracy, when suddenly his body is filled with a surge of energy from outer space thus erasing his personality and transforming him into a modern wargod, complete with Mohawk hairdo mimicking a Roman helmet crest.

This transformation is accomplished, in a burst of Kirby technobabble, via “electronic surgery — a computer hormonal operation done by remote control!”

For, unbeknownst to Buddy, the faceless officers of the Global Peace Agency have selected him to be imbued with the immense powers of OMAC: the One-Man Army Corps.

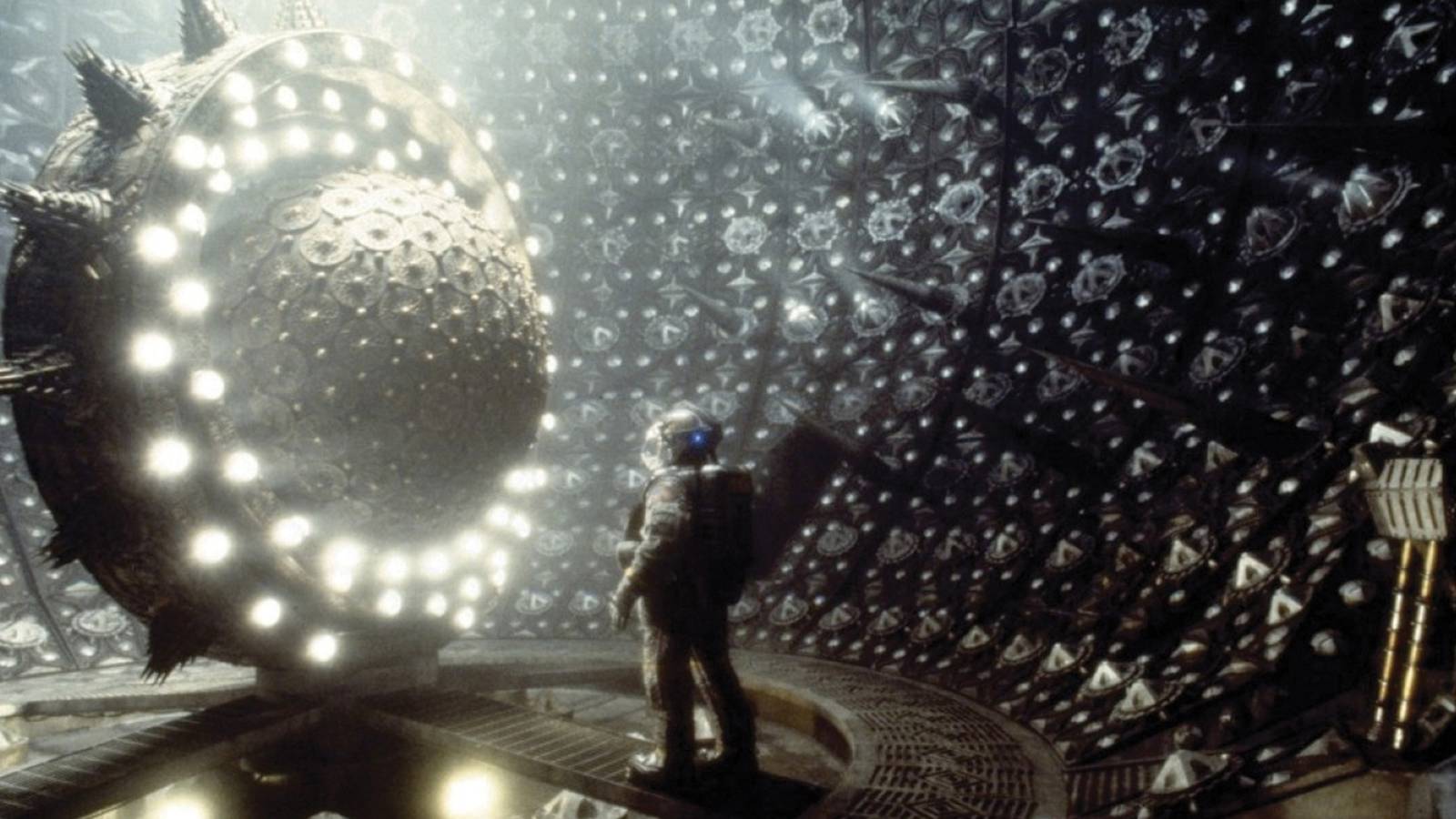

A machine named Brother Eye (described only as “the most advanced and complex piece of metal in this dangerous age”) has been constructed by a NASA scientist as an orbiting satellite and is able to track and watch, advise and aid OMAC. Brother Eye, ever observant, is able to alter to his body by means of invisible energy beams and grant him various ill-defined powers as need arises. OMAC and the Brother Eye satellite are permanently linked, and close as brothers, hence the name.

OMAC defeats the corporate thugs and their deadly traps in a running battle, then fills the factory with an unexplained radiation that triggers a series of explosions. He says a sad farewell to Lila, who is, even to the last, is gushing over how nice he is, and she would like to be his friend.

As explosions level the facility, OMAC walks away into the night, never looking back, musing grimly on technology’s inhuman ability to blur the line between machine and man.

Thus OMAC is born.

The run is so short, the a few paragraphs will sum up the whole work.

First, OMAC faces criminals so super-rich that one can rent an entirely city for a day of celebration, but actually fill the streets with killers in clown suits. Plausible or not, the idea of rich men so rich that one could rent a city is striking, and reflects on the anxiety of growing inequalities of wealth.

Within the city, OMAC is led to the apartment of the NASA scientist who created him, who is immediately murdered. The matter is handled so abruptly and with so little emotion, that one assumes this was done merely for the same reason the doctor who created the Captain America super-soldier serum was killed, namely, to quell readers questioning why squads of such folk were not created.

The next case is unrelated. Another criminal gang is kidnapping healthy and handsome youths and damsels whose bodies dying crones and degenerate octogenarians will usurp by means of brain transplant.

A street-thug named Buck Blue orchestrating the kidnappings is forced by OMAC to become his sidekick, turn informer, and trace his victims to their ultimate destination, and unmask the top boss: when the unwilling sidekick discovers his own girlfriend is about to brain-swapped, he is outraged. But then he is bribed, forgets his outrage, attempts to betray OMAC, but fails. Faceless peace officers arrive and stun everyone with sleep gas. Arrests all around. So, not quite a happy ending for Buck Blue the sidekick street thug. But the girl lives.

In his third case, a warlord with a private army is too powerful for any ordinary army corps to combat, is menacing world peace. But OMAC, the one-man army, is able to overcome his army with a single flying war-chair. OMAC penetrates his mobile super-fortress and to arrest him, returning him to Mount Everest (the headquarters of the Global Peace Agency) for computerized booking and trial.

The warlord in retaliation unleashes his atomic-powered genetically engineered flying super-monster, the multi-killer, which OMAC wrestles in mid air. OMAC breaks one of the monster’s tusks. The monster goes blind, soars into the stratosphere, and blows up for no apparent reason. I reread the scene three times, and there is no explanation.

His final mission is to track down a criminal super scientist using the same type of atomic restructuring technology as grants OMAC his powers to drain the world’s oceans.

The final issue is a hastily-contrived trainwreck. After spending many pages meeting the evil scientist, his beautiful daughter, and her empty-headed boyfriend, OMAC is robbed of his power by an energy beam before he even reaches their underground island base. He returns to the form of a bewildered Buddy Blank with no memory of OMAC. Blubbering and confused, the hapless Buddy captured by the evil scientist and is never seen again.

The Brother Eye satellite and the evil scientist engage in a duel of super-science beams from surface to orbit and back again. After an absurd scene where Brother Eye throws furniture at him, the evil scientist imprisons Brother Eye in a stone cocoon. The machine is helpless. In the final line of the final panel we are told, but not shown, that the hidden base of the evil scientist overloaded and blew up.

The end was so abrupt and absurd I had to read it twice. It first, I thought the Brother Eye satellite, as it was encased in stone, fell out of orbit, made re-entry, and crashed into the island base in an act of ironic mutual destruction, a death the scientist brought on himself by pulling the satellite down on top of him. No, this was merely a trick of my baffled brain: the text says no such thing, nor do the panels show it.

Such is the sad fate of a work by an overworked genius whose contract abruptly ended.

(Not to worry, true believers! In KAMANDI Last Boy on Earth #59, OMAC reappears in a back-up feature. He and Brother Eye recover from the defeat. It is established here that OMAC is in the past of Kamandi, which is a PLANET OF THE APES homage taking place after a great disaster wiped out human life and uplifted myriad animal species to semihuman form. Which means, sadly, the OMAC does eventually fail in his mission to stave off the end of civilization.)

As for the characters, sadly, aside from the mohawk and a lidless eye emblem, OMAC and all his cast and crew are both inconsistent and forgettable. This perhaps could be the fault of the brevity of the run, only eight issues, but more likely it is due to the haste and lack of care brought to the work, the lack of editorial oversight.

Buddy Blank literally has no personality traits aside from being an empty and alienated target of bullying. He is not Steve Rogers, 4F, too weak to serve his nation but so patriotic he is willing to volunteer for a dangerous experiment.

If anything, Blank is the mocking opposite of Rogers. He is neither consulted nor warned. The fact that Buddy is being exterminated and erased by the one-way OMAC transformation process is under-emphasized, almost unnoticeable.

It is mentioned in passing that Buddy has one last thought as himself before being quenched into the war-god persona of OMAC, without any mention before or after that Buddy was not meant to survive the process. There was neither foreshadowing nor follow-through to his plot-point, which should have been crucial but is, in face given less space in panels or text than the “psychology section” where employees kick robots in the rear.

Buddy Blank is not Billy Batson. He does not change back into a mortal man during his off-duty hours. But the fact that he is erased (or, at least, rendered comatose) by the transformation is as horrifying as any of the brain-swapping or build-a-friend technologies he fights against. If Buddy had any friends or relation to note his sudden disappearance, they are not onstage. neither the NASA scientist nor the faceless peace agents dwell on, or even discuss, this side effect of their project.

This is simply bad writing: either Kirby is attempting a sly trick of leading the reader to root for an anti-hero, or he himself failed to think through the implication of the conceit of the story.

Because the fate of Buddy Blank is not brought up again. OMAC does not sit in the rain atop a cathedral gargoyle and brood on the fate of the young man who had to die to bring him to life. He occasionally mentions having no memory of his past life, but expresses no curiosity, no discontent, about his current life.

He is willing to live in whatever quarters and with whatever parents the computers assign to him.

OMAC himself has no personality traits, aside from a willingness to fight, and a certain “Dirty Harry” police brutality he brings to bear on the criminals in the World That’s Coming.

His quips are really not that quippy, and he has no slogans nor warcries to call out: it is never clobbering time. He has no particular way of talking, neither the scientific jargon of Mr. Fantastic nor the faux Shakespearean antiquity of Thor.

OMAC has no love interest, no Lois Lane seeking to discover his secret identity and trap him into marriage; not even a Big Barda to serve as a foil to his foibles.

The closest we have is Lila, the fem-bot he destroys in episode one, but he never remembers her later. Discovering your only friend was a wax dummy that you yourself must murder should have been more dramatic, if not traumatic. But this is the trauma that extinguished Buddy Blank in his last moment of self-awareness.

OMAC never mentions her again. Before we say the comic art form is meant for a juvenile audience, hence is not meant to dwell on deep psychological trauma, I will point out that Ben Grimm (invented by this selfsame author) dwells on the space-radiation accident that created him quite frequently, and his bitter grief at his inability to live a normal life is the central conceit of the character.

OMAC has no sidekick, except briefly, in one episode, a snitch whom he forces to aid him, who turns out to be willing to sell his girlfriend’s body into the hands of murderers for money. This sidekick is ironically named Buck, perhaps meant as a sly subversive parallel to Bucky, the sidekick of Captain America.

OMAC has no family, no private life, no secret identity, no off-duty hours. We are introduced to a childless married couple in one of the most disturbing scenes in this disturbing work, who have been rented or assigned to be his parents, but, unlike Ma and Pa Kent, they have no personality. The plot immediately forgets them.

The NASA scientist who appears in episode one and is assassinated by episode two likewise has no discernable personality traits, aside, perhaps, for pride in his work. I did not even bother to look up and repeat his name in this review.

Let us note the contrast. In Jack Kirby’s MISTER MACHINE (later, MACHINE MAN) who first appeared in 2001 A SPACE ODDESEY there is a scientist named Abel Stack who raised the self-aware robot as his own son, when the other fifty self-aware robots in the project, not treated with fatherly love, suffered from identity crisis, and went mad. The order is given to destroy them all. Dr. Stack defies the order, and dies while saving his robotic son from the self-destruct mechanism implanted in his computer brain. Dr. Stack has the same amount of time on panel as the NASA scientist here, but his name merits being remembered, because he is portrayed as noble. NASA scientist guy here is merely another blank.

The faceless peace agents are literally faceless, hiding all trace of race and national origin behind a cosmetic spray, (much like Vic Sage in Steve Ditko’s THE QUESTION), in order to appear non-partisan, favoring no nation.

Absurdly, after creating OMAC and granting him the rank of a five-star general, able to requisition any gear and give any order, and setting him free to maim and batter bad guys worldwide, topple tanks and wrestle atomic monsters, we are told the peace officer themselves are not allowed to carry firearms or to harm human beings in any way: all their weapons are non-lethal, such as sleep gas or sticky nets.

So the peace agents are not allowed to hurt humans, but they are allowed to erase Buddy Blank and change into OMAC without a warrant. Again, this is an inconsistency of tone, a sign of sloppy writing, which a good editor would have caught and corrected.

No peace agent is given a name nor has a recurring role. The vividly stereotyped Howling Commandoes of Sergeant Fury they are not.

Likewise for the villains. None has a distinctive look, or evil power, or schtick. The names are silly but apt in the classic Kirby style: Mr. Big, the Godmother, Marshal Kafka, Fancy Freddy. OMAC is fighting gangsters, ultra-rich criminals, warlords, terrorists.

The World That’s Coming has no glamor, no heroes, only biotechnological monsters, some controlled by the secret police, some not.

Another inconsistency of tone is the legality or lack of it displayed by OMAC. He is said to be an officer of the law, a five-star general, in fact, whose orders will be obeyed anywhere in the world, but the peace agency does not seem to have the clout to back it up.

For example, when OMAC is first created, he is already in the field, in a robot factory of which the peace agency is suspicious. He immediately claims to have authority to condemn and demolish the place, but there is no legal process here, no arrest, no warrant. OMAC is not granted legal authority to do anything until a later episode. He just shoves through any opposition, enters private property, beats up suspects with aplomb.

OMAC is mugged by unformed armed guards wherever he goes, both inside robot factories and along the streets of cities rented by the super rich. In the World That’s Coming, every criminal gang and warlord has more soldiers and gear than the peace agency, and can fill the subway with genetically mutated monster-men called Sickies.

It is never stated that the Global Peace Agency is part of a world government, or is the secret service of a superpower, or is an offshoot of NASA. On the other hand, OMAC refers to constitutional rights, and captured warlords are held for trial, so the Anglo-American tradition of trial by jury may still be lurking somewhere in the background.

And it is stated that large armies are outlawed, so perhaps that is the reason the remaining armies apparently are in criminal hands. When the law outlaws armies, only outlaws have armies.

These outlaw armies form forces OMAC can meet and match and overmatch, being a one-man army corps. Hence the name.

And yet the legal system of the World That’s Coming is somewhat vague. The world government, if it exists, also lacks personality.

Or perhaps Kirby never made it up. The World That’s Coming is a mere mishmash of 1970s anxieties projected into the near future.

The lack of personality traits on the characters may be deliberate: none of the victims of Big Brother or the World State in Orwell or Huxley have personality: each is meant to be an ‘everyman’ figure, a blank into which the reader can read himself. The theme here is that the future technology will denature mankind.

And so men robbed of humanity occupy the stage. Such is the theme of the work, and the theme is not forgettable at all. It is haunting.

The grim tone is not found in any other work I have read of Jack Kirby: imagine if the New Gods stories only took place on planet Apokolips [sic], with no New Genesis.

Even in minor asides, the future shock anxiety is present: for example, it is mentioned in passing that magnetic motorcars have replaced the internal combustion engine (“New emissionless vehicles glide on waves of polarized force”) due to the energy crisis.

For those of you who do not recall the 1970s, when the Carter Administration reacted to Arab Oil embargoes by imposing rationing, this absurdly abundant national resource was suddenly scarce. It was not politically correct to identify the actual source of the shortage (due solely to political policies) and so the public was convinced that the world would soon run out of fossil fuels — at that time thought to be a non-renewable resource. Like the fear of overpopulation, these bugbears of days long past now seem quaint.

But not all of the future shock anxieties portrayed in OMAC seem so quaint these days, but instead are eerily prescient.

The work is peppered with examples of dehumanizing technology. Films can be fed directly into one’s brain as an illusion to deceive all five senses, or firing ranges equipped with lifelike holograms, lonely men can buy lifelike animatronic comfort women.

Instead of computerized matchmaking young couples for marriage, a government agency helpfully creates artificial families, mixing and matching grown orphans with older couples who lack children.

Disgruntled corporate dummies are encouraged to visit “the Psychology Section” to let off some steam in a “Crying Room” or a “Destruct Room” where to kick mannikins, smash furniture, or set cars on fire. Ask yourself what kind of society finds such things entertaining: it is horrifically similar to ours.

There is, in fact, not a single normal human relationship on display at any point in the “World That’s Coming” — marriage, family life, romance, child-rearing, a sense of small-town community, nothing like this is shown.

There is a recurring flaw found in anything Jack Kirby did without an editor like Stan Lee present. Kirby never establishes what his superhuman characters can and cannot do.

This seems to be merely a lack of discipline on the part of Kirby’s muse. Any fan could easily list the powers present in the Fantastic Four, or say what was special about Captain America’s shield. That Jonny Storm, the Human Torch, can be quenched with a firehose or when caught in a vacuum chamber needs no explanation.

But OMAC’s abilities vary each time Brother Eye blinks: he is super-strong and bullet proof, except when he isn’t, when he has to rely to his speed to dodge bullets.

Brother Eye can protect OMAC and anyone in the room with him by a “heavy-elemental beam shield” from a sniper’s missile strike, except when he cannot, and snipers can shoot the NASA guy dead in cold blood.

Brother Eye can dissolve bullets in flight with laser beams, then place OMAC in a coma indistinguishable from death, and alter his body to seem to have a death-wound via long-distance genetic surgery, except when he cannot.

Brother Eye can lower his density to allow OMAC to weigh less than a bird and leap immense distances, except when he cannot, and OMAC has to risk his life leaping into an air vent whose upward blast of wind cushions his fall.

Brother Eye’s beams feed directly into OMAC’s brain, except when they don’t, in which case they are transmitted into his belt buckle, or the lidless eye emblem on his chest.

Indeed, I do not recall as single energy beam gimmick used by Brother Eye that is ever used twice. Certainly there is no stated limit to the power: why OMAC cannot call upon instant remote-control electronic surgery to disguise his face, or have himself altered to breathe water, or levitate, or resist electricity, is nowhere stated.

The gizmos and gimcracks carried by Scott Free, the super-escape artist, have a similar ability to come and go as the need requires, as do the power of the Forever People, or any of Darkseid’s minions. Jack Kirby was just not good of establishing a conceit and sticking to it.

As a writer, Jack Kirby’s genius is, sadly, too energetic, and too unfocused when Stan Lee is not present to rein him in and keep the high-level concepts grounded in normal human life. This was the reason why the Fantastic Four was unforgettable, and OMAC is forgotten. Kirby needs an editor.

For all that, OMAC the One-Man Army Corps is freakish, absurd, disturbing, and larger-than-life.

Fans of Jack Kirby should definitely read it; for those not ready to absorb the overload of over-the-top operatic awesomeness that is Kirby when Kirby goes dark, your mileage may vary.

******

Originally published here

English (US) ·

English (US) ·